Chapter 7 Sawmilling, Land Development and Mineral Exploration

In the early 1950's I began sawmilling and land development at Takone, in the North-West of Tasmania. I was in shares with various partners in sawmilling and with Donald and Mew McLennan in the land development project.

However, before I began sawmilling or had even built the sawmill, four of my five partners withdrew, leaving me with the major job of financing and constructing a modern sawmill and a road to the Arthur River and elsewhere. Logging and sawmilling could not begin without an access road into the forest.

Finishing the road was a financial necessity, because I had had to pay out the four partners who withdrew, and had I not finished it successfully I guess I would have been bankrupt.

My remaining partner in the sawmill venture told me he considered my financial estimates were optimistic and the possibility of finishing the road extremely doubtful. And, he pointed out, if the six original men, most of them having money and experience, could not build and finance it, there was no hope for two of us.

So, he argued, supposing all my optimistic figures to be correct, we would still be £60,000 short of cash, which in those times was a fantastic amount of money.

As this was affecting the health of my partner and he was not much moral support, I arranged to pay him 50 per cent extra on the amount he had invested if he would give me three years to pay it back. This was done and I started to build the sawmill, which eventually became a great success.

Generally in most businesses, if a partner is not a help to you he is a hindrance, because of the necessity of discussing plans and agreements. Often each partner unwittingly leans on the other, and sometimes nothing is done. If you have an accident and use a crutch, throw it away when better or you will continue to lean on it, and forget to stand on your own two feet.

When I was up to my neck in the project I offered Alstergrens,

who were major timber sawmillers, a half interest in it at cost, for I

realised I would have a very big job to finish it with my own resources.

Alstergrens inspected the project and decided that, under no circumstances,

would they invest any capital. However, I did finish the road

successfully and I also built the mill. Then Alstergrens asked whether

they could buy into it. But I took the advice of my old Scottish Uncle

Don, who said, If a man will not help you with the pull of the oars

when the river is rough and the current is against you, you do not need

his help when things are going well and you are floating with the

current

. I refused the offer.

I received no encouragement in regard to the building of the access road also. For instance, the Government considered it impossible to build this road with an 8 per cent average grade and a 10 per cent maximum. I was to be granted £14,000, about one-third of the cost, after it was built if I could construct it to the above specifications. It was a problem, and I did a lot of surveying, blasting and drilling personally.

Once I went to stay three days and, because of problems, kept ringing Peg and extending my stay. I sent the foreman for a holiday and stayed six weeks, during which time I used about eight cases of gelignite and got through the difficult area.

One day, while we were trying to negotiate a difficult bend of the road, we had a number of visitors from other sawmills, plus members of the Forestry Commission, who were talking to us while the bulldozer was operating on this very steep country.

One of the bushmen asked me to pass him an axe from the bank. I turned around, picked up the axe, and as I turned back I heard a terrific roar. The bulldozer and driver, Tink Taylor, and most of the road and the side of the hill, with trees growing on it up to 200 feet high, had disappeared.

Looking over the precipice, we could see the bulldozer was still upright, about 30 feet down over the edge of the road. It did not seem possible - it had all disappeared in a flash. The dozer driver was not hurt and, after discussion, he suggested that he put the winch on to a myrtle tree higher up the bank and winch himself and the dozer straight up in the air and hopefully over the edge on to a small flat section of the road still remaining.

He was to watch me and I had to keep my eye on the tree to see whether it would withstand the pressure. If I could see it would not, I had to drop my hat and he would release the winch and, with luck, hurtle down to his original position.

As the dozer began to be winched up the precipice the tree began to bend. The nearer the bulldozer got to the top, the more the tree bent and I was almost ready to drop my hat when the machine balanced over the precipice on to flat ground.

All the seven men present let out their breath 'Phew!' It was a very close go. The dozer driver had shown tremendous courage and it had paid off. Perhaps, looking back on the exercise, it was a bit foolhardy, but we were battling against time and money, and everyone knew it.

There were many incidents which were nearly tragedies, but fortunately they turned out all right.

One day I was on a hill in the bush looking across to where road construction and tree felling were going on. Roy Shepherd was felling a giant hardwood and the dozer driver, Jack Taylor, brother of Tink, was also working close by, although he should not have been in the area while the tree was being felled.

Roy was a wonderful bushman, but somehow a fault in the tree or a sudden gust of wind, or both, made it begin to fall backwards. I watched in horror while Roy tried to jump out of the way, but his feet caught in vines and he fell down. I realised that the bulldozer also was in the path of the falling tree.

The driver saw the tree coming, jumped from the moving machine and escaped unhurt as the tree smashed down. The dozer was completely smashed and was later sold for parts.

I rushed across to see what was left of Roy, who was under hundreds of tons of hardwood, to find he was still alive. Miraculously, he had fallen into the one little natural trough in the ground in that vicinity. We untangled the vines and got him out; he did not have even a broken limb!

The tree had made a hole 18 inches deep in the hard soil, but Roy's hollow into which he had accidentally stepped was deep enough to protect him. It was very close. Both his legs swelled up, but no bones were broken.

Another incident concerned Biagio, a former Italian P.O.W. who returned to Australia after the war and worked for us. He was cutting down a big myrtle tree for the sawmill when I happened to be in the area. Biagio was a very powerfully built man with big thighs and arms. He staggered on to the road as I drove up the bush track with blood pouring from an arm and a thigh.

He had been felling a myrtle on a [*]shoe about eight feet up when the tree, again through some defect, fell backwards. The chainsaw Biagio was using cut him badly during the fall. His leg was a shocking mess, cut right into the bone.

[*A shoe is the name for a plank inserted into the trunk of a tree.]

I drove him very carefully to Mr. and Mrs. Edgar Barrett's home at the Takone Post Office, feeling each little bump on the road myself, because Biagio's wounds would open and close with the slightest jar.

Mr. and Mrs. Barrett had lived alongside sawmills for years, and Mr. Barrett wanted to know how the chainsaw could cut both the man's arm and thigh. Biagio, as an illustration, jumped up and fell down; his cut thigh flapped open wide and blood poured out, but Mr. Barrett still couldn't quite understand. So Biagio gave another demonstration, flesh opening and closing and the bone being exposed! I thought of howl had been driving so carefully to avoid jarring him. He was a very tough man.

After I agreed to buy out my other partners a Melbourne company paid for £12,000 worth of timber in advance and I agreed to sell them so much timber a year for a period. They were a good firm, but always very slow with their payments. I really felt they used my capital to help finance their projects. This policy is very hard on anyone getting established and short of money, as I was.

Later, one of our biggest timber companies signed a two-year agreement with me for the purchase of timber at a fixed price (there was very little inflation in those days). The manager rang me one Monday morning to tell me off, in a friendly way, because he said I was 30,000 super feet behind with my weekly deliveries. However, on checking I found 45,000 super feet in their yard that they had not stacked. On Thursday of the same week the company told me that, with the depressed state of the industry, they could not take any more timber, although it was under contract. On the following Monday they informed me that they could not even pay me for the 45,000 super feet in their yards not racked. In fact, they did not pay me for this for about thirteen months.

The manager was very sympathetic and nice and said I could deliver under my contract, but he was not allowed to pay me. While the company had plenty of money for expansion of their industry and for fighting court cases, the directors had decided they had no money for payment for timber, even under a legal contract which they had drawn up!

I found through my working life that a contract with a big company is not worth the paper it is written on, as they have a tendency to break it, if it is in their interests to do so. But, with their power, they will force you to keep your part of the contract.

I had the same experience with another company. I had made an arrangement with the manager and the secretary to buy all my sawmill construction timber from their sawmill division and pay for it in three months, as I was very short of cash at the time. The manager and secretary were very pleased with this arrangement and the very big order, but upon delivery the company requested payment for the timber in seven days. This was another example of how big firms try to put pressure on the smaller people.

I built a lunch room with washing facilities for my men, and up until that time, this was considered an unnecessary luxury. I attended a sawmills meeting soon afterwards and the majority of members condemned me for my extravagance, saying it would then become a necessity.

I pointed out to them that the men worked very hard on the one job for twelve months and became hot handling the very heavy timbers. Apart from the humanitarian viewpoint, from straight-out business considerations it was essential to make it unnecessary for them to sit down in a draughty sawmill where they could catch colds, with resultant interruption in production. Later on, the workers quite rightly demanded a place to eat out of the draughts and sawdust and somewhere to wash their hands.

Our sawmill at Somerset was a big, modern plant with the first edge timber sorter in Australia; later A.P.P.M. copied it for their own use. We also had one of the first private wood-chipping plants installed.

I asked an opposition bank for a development loan of £7,500 to install this sophisticated timber sorter, but they would not lend me the money. So, after I had financed it myself and did not require any money, I wrote to the chairman and said it was a pity his bank could not implement the progressive policies he personally broadcast.

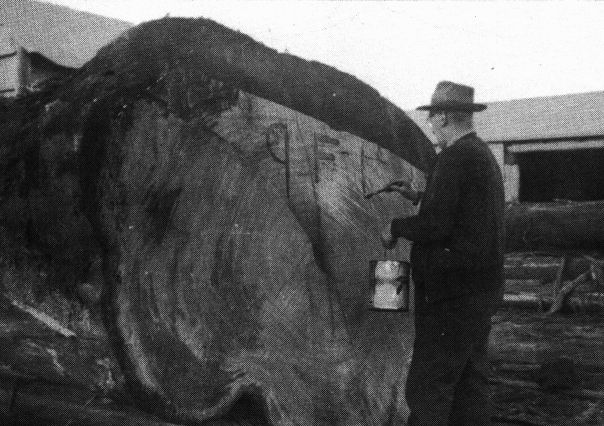

I was immediately offered the money, which I did not then need, nor did I need their help. But I thought my comments might help others to procure money under similar circumstances. We had made a good job of building the mill. 'Tell' Cameron was in charge. We used extremely powerful motors on the twin saws, which gave our boards a good, straight finish. Even very big trees did not slow the twins, as happened in most other sawmills at the time. I think the biggest tree we cut from the bush - and there were a lot of big ones - yielded 23,000 super feet of timber. It was a log 9 feet 3 inches in diameter.

'Tell' Cameron, sawmill manager, with the biggest tree we cut from the bush,

yielding 23,000 super feet (69 cubic metres) of timber.

It was a log 9 ft 3 ins (2.8 metres) in diameter.

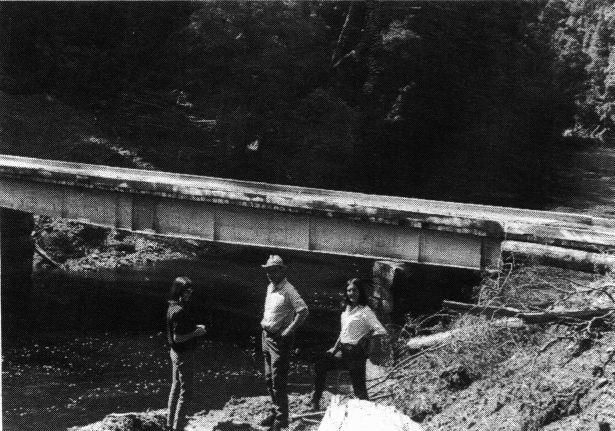

To service my sawmill I had to bridge the Arthur River at my own expense, and it was a major project. The Forestry Commission had just finished putting a bridge over the Arthur River some six miles downstream, at a total cost of about £500,000.

I was fortunate in having good men, and procured the services of Ken Brown, a really good bridge builder. We secured second-hand a long steel bridge from the Hydro-Electric Commission, put concrete piers in the river, used the steel in the centre and built wooden ends, making a good, strong bridge over the 200 foot wide stream.

The first load of logs to go over it weighed a total of well over 35 tons.

The sawmill and leases were sold to Associated Pulp and Paper Mills in 1973. The bridge we built is still being used today and the road is officially called Farquhar's Road.

The land development scheme also was quite a big one. Again the partnership split up and I ended with about 2,500 acres of chocolate myrtle soil, which was very productive.

Doug Fenton was farm manager at this time and his wife Margaret looked after me when I was working hard on the road. Doug had five to six men working permanently clearing old rotted logs and fencing, but they were disheartened by the mammoth task ahead.

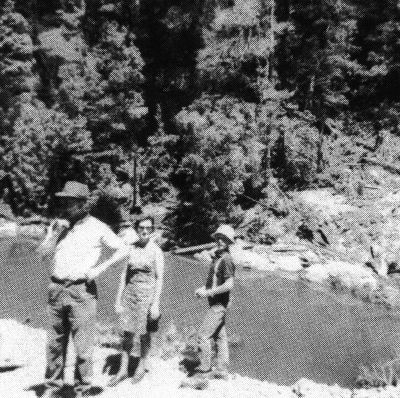

Peg, John and I checking the Arthur River for the best site

to build a bridge in the late 1960's.

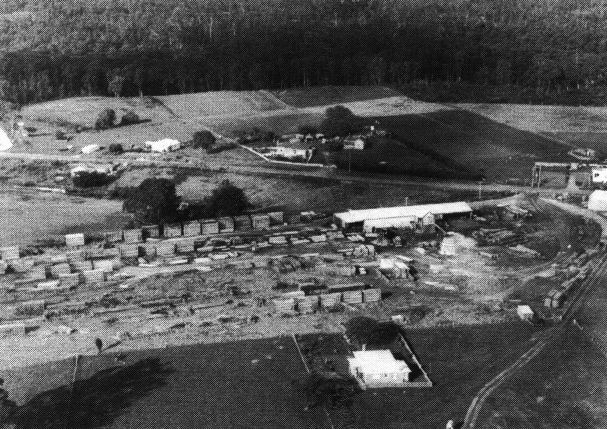

My sawmill at Somerset with Australia's first edge timber sorter installed.

Everything built and planned by myself with practical helpers.

To help them, during a two-month period I organised six Saturday working bees.

I was at this time managing director of Dewcrisp, and would leave Scottsdale on Friday afternoon and return on Sunday. The men would travel from Burnie to Takone by bus and spend the day picking up wood etcetera. The average number in each working bee was 102 men, and Bob Tatlow, who owned buses at Burnie, transported them to work and back to Burnie, about 20 miles (32 kilometres).

Many of the men came from A.P.P.M., where they worked shift work in the factory, and they were thrilled to have a day out in the open air with a hundred others, lunching and swapping yarns.

I paid the truck drivers for a day's work and, of course, Bob paid them for driving the buses, but the buses were left on the job, which made it cheaper. I paid the men £3.0.0 ($6.00) for the Saturday work.

Bob heard two of the men talking in a hotel saying there were so many men on the job that they had gone fishing for the day and then collected their wages - and no-one knew. I think this may have been just a little bit of skiting over their beer, but when Bob was signing on men for the following week he told these two men they were not wanted, for we were not paying people to go fishing! They were taken aback.

A Mrs. Diprose had a property adjoining our developmental area, but she lived some miles away. When I suggested we take a short cut through her property, my foreman said it was a risk - we could get shot - but I thought we would chance it.

I thought he was exaggerating, but when I saw tin cans strung on wire with bullet holes through the centre where the 60-year-old widow had been practising, I realised it was not such a joking matter.

Another of my men, who was driving his car to Burnie, stopped

in front of Mrs. Diprose's place, and had his head under the bonnet

when Mrs Diprose fired a rifle shot through the bonnet from the house

some chains away. Ken called out, You silly old thing, you nearly

shot me.

Sorry Ken

, she replied, I thought you were a stranger

.

The Arthur River bridge built by myself in the late 1960's.

Ken Brown was in charge of construction.

Daughters Sue, Mary and inc in front of completed bridge.

My dozer driver, Mr. Wally Falls, was a great character and a really good man. However, I was annoyed to find out that he had missed two really good days, apparently doing manual work for Mrs. Diprose. I asked him for an explanation and he told me Mrs. Diprose had complained to the police that people were listening to her telephone conversations and she wanted a new telephone pole put up so they couldn't hear! The police had asked Wally to humour the old lady and put up the new pole. Hence the reason for his absence.

I am admiring bulls in foreground.

In background is an experimental plot of pines

planted on ground we developed for farming at

Tacone, North West Tasmania.

It was sold and now this whole area is growing pines for A.R.P.M.

Wally was a great character and used to dive into the bushes or scrub to catch a snake. He went into a Burnie hotel one day and got a lot of chaps talking together, leaning over the bar. He then picked up his sugar bag, untied the top and tipped out the contents on the top of the bar. It was a great live poisonous snake, which landed close to the faces of the patrons. Wally thought it a great joke, but some of the others were not amused.

I have seen Wally pull up his bulldozer in thick ferns and jump off to grab a snake. He would jump up in the air about three feet, the snake also rising a couple of feet in the air; then he would dive down again and bring the snake up in his hand.

Another day a farmer went to get chaff from his chaff house and in the semi-darkness a snake hissed at him. Wally ran in, searched around and came out with it in his hand.

He was very much admired by members of the opposite sex. At times I thought this might be detrimental to my business dealings, but then again it might even have helped!

This land at Takone was sold to Singline in 1973, and now A.P.P.M. has it all under pine plantations. Mr. Singline was chairman of Tasminex, a company which thought it had found a lot of nickel. Some people thought him not a 'straight shooter', but I believe he was, though an optimist.

About 1958 Doug Fenton, manager of 'Braeburn' our property at Takone, and I did a three-day trip up and back in the bed of the Keith River, even though old Mr. Barrett, the West Takone Postmaster, said no-one had done it before, as it was impossible.

However, a very dry summer and an exceptionally dry February made it easier. Even so, we cut things pretty fine, for we ran out of food and in the last 24 hours we had only one dried apricot and a date between us. We had some hair-raising experiences and were lucky to get back alive. It taught us a lesson, for it was an almost impossible task for two people to undertake. There should have been at least three men in the party, so one could stay and attend an injured person and the third go for help.

We never ventured through that area afterwards without three men, and those who have experienced horizontal scrub would appreciate why. Sometimes you would either have to crawl on the ground beneath the horizontal in semi-darkness or walk along the top of it for hours without touching the ground. There is no way you can go through the horizontal, as it grows up in the air and then falls over, but keeps on growing.

We had some very hard trips over a period of 11 years in this mainly unexplored country, each lasting three or four days.

To give an example of the risks involved in the Keith River trip, the last two bushmen, who left Corinna some 47 years before to get to an old chap who still lived at Takone, disappeared and their bodies were never found.

In the dams debate of recent times I was amused to hear it said that the Franklin River was the only wild river left in Tasmania. That was a wild exaggeration! The Keith River, while smaller, is certainly a wild river, and there are others, such as the Lyons.

Doug Fenton and I were really looking for minerals. In early 1890, silver lead claims were granted in this very difficult country to Pyke Brothers and others, apparently as a reward for finding rich mineral in a new unexplored area. This mine was known as the Atlas Silver Lead Mine. My secretary and I worked out a scheme to pinpoint the suggested mineral deposit. We bought 24 rolls of pink toilet paper which was unrolled into metre lengths. A stone was secured in one end of each length with a rubber band and the streamer was wound up around the stone.

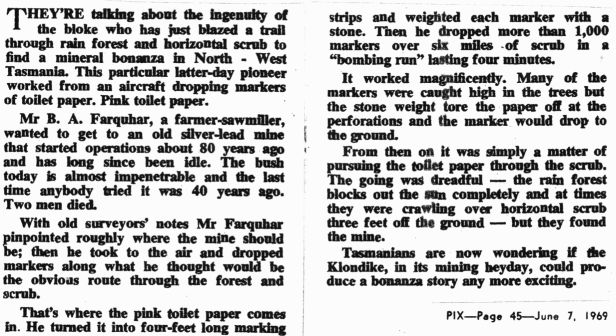

A friend and I did some trial runs dropping them from a plane as fast as we could onto a possible route which we could use to reach the mineral deposit. This is how the magazine, 'Pix', described the operation:

PIX - page 45 - June 7, 1969

The scheme worked perfectly, the paper unrolling on its downward fall and catching in the tops of 200 foot high trees. Then a perforation would give and fall another 20 feet, and another tear in the paper take it down further until it eventually hit the ground. We had only to walk through the bush and keep in sight the line of pink toilet paper, which had dropped about half a chain apart. This proved time- consuming, but successful. We found tens of millions of tons of iron ore, but our hopes for a possible nickel deposit failed.

The fording of the Keith River.

We were dozing a track to our mineral find on the above slopes.

In 1969 my son John, aged 11, came with us on the four-day trip and did a fantastic job carrying his swag from 5 a.m. till 7 p.m. (14 hours). He would not let me carry his swag because I had said that everyone must carry his own swag. A creek is now officially called Johnny's Creek, because he wanted to walk over a round moss spar 30 feet in the air and I would not allow it, because if a leg was broken it would be extremely difficult to carry a person out. It was no easy task to provide access to the mineral deposit.

The second day out on this trip we were up very early and after breakfast left at daylight. Charlie and Kevin Pinner were, the other members of the party, and Charlie was to carry the food. About six hours afterstarting Out early in the hopes of reaching a high peak we were famished and sat down for a good meal.

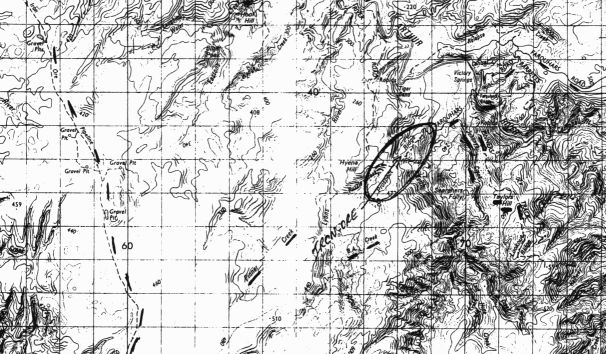

Map showing Farquhars Road and Bridge.

Mining area - Johnny's Creek, Pinners Track and Taylors Hill.

Unfortunately Charlie had picked up the wrong bag in the dark and all we had was one apple between four and a five-hour trip back to base! I don't ever remember being so hungry, but John said afterwards, 'Dad dived down to the ground and rescued an apple pip he had dropped!'

It teemed with rain that night, and all the cover we had was a plastic white sheet spread above us. John thought his Dad was very generous stoking the fire all night long, but I was the furthest from the fire and it was the only way I could keep warm in the cold autumn weather.

Johnny was a terrific little chap, and he used to think I was fantastic. I think that as he grew older he had to realise that Dad was just a normal human being, but at the age of two or three it was different. He used to put his feet in my boots and put on my hat, because he knew I would never go anywhere without them. So he came with me everywhere, including the stocksales.

I remember one day when he was sitting up on top of the sale yard

fence and the auctioneer said, 'What am I bid to start off this pen of

cattle?' John said, £35 and all the men laughed because they were

only worth about £17 at that time. He was very upset, although he was

only a wee chap. He said to me, All the men laughed

. I said, Oh

they thought you were only just having a joke with them, because they

were only worth about £17

. So then he was quite happy. He did not

like being laughed at when he was a little fellow, because he was so

interested in the cattle and later became a very good judge of cattle

values.

I was out on the farm with him one day when he was about eight.

He said to me, See that wild duck in the big pond; I can dive in and

catch it

. I was a bit tired and said, Don't be silly boy; you couldn't

do that

. With that he dived into the water, swam underneath, came

up and caught the duck.

That is only one chance in a million

, I said. So he freed the

duck, which was only young and could not fly, although it could swim

quite well. Johnny then sneaked over the other side of the pond and

got under some shelter; then dived in, swam underwater, came up and

caught the duck again. So I had to say, Well, it is not just one chance

in a million now

.

He was a fine horse rider, but when he asked me whether he

should pay $100 for a horse that no-one could ride I remarked, Well,

it is your money, but it is no use paying that much for a horse if you

cannot ride him

. If I pay $100 for a horse I'll ride him

, he said,

and he did. Before he was drowned he had made the horse a really good

stock mount. Later, after we lost John, I rode this horse sometimes and

found it really good.

John lost his life while Peg and I were in China in 1976. He was duck shooting and went to row across a lake. When his companions looked around he had disappeared. We don't know what happened, but evidently he overbalanced backwards and the shock of the cold water caused him to have a cardiac arrest.

I was quite surprised, when the autopsy was done, to learn that most of the drownings in Tasmania were really cardiac arrests. In many cases, the doctor said, you can get the heart going again by putting your hand over the heart and giving it a hard thump, even though you may break a couple of ribs.

Although John was used to swimming in the cold water in the middle of winter, each time he dived in he knew what he was doing and was mentally adjusted to it. Apparently if you do not know what you are going to do, you are not mentally adjusted to it and you can die of cardiac arrest.

John had no water in his lungs at all when his body was recovered. We got back from China in two days, and it was another five days before his body was recovered. It was a great tragedy for the family. John was in his nineteenth year, and was a wonderful swimmer.

Farquhar family taken in about 1959.

Back row, left to right: Helen, Mary.

Front row: John, Jeannie and Suzanne.

John (right) and a Pony Club friend at the Scottsdale Show about 1967.